[s. a.]. 1936. LIFE.

Article ReMix

Looking at Me by Looking at You: Imagining French Gender Roles through « Paris Match »‘s Everyday American Woman, 1949-1955

![Auteur inconnu. 1949. «Phyllis Nelson est une Américaine comme les autres» [Reprographie]

Tirée du Paris Match, No. 25 (10 septembre 1949): 26-31.](/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/1a_correction-scaled.jpg)

Auteur inconnu. 1949. «Phyllis Nelson est une Américaine comme les autres» [Reprographie]

Tirée du Paris Match, No. 25 (10 septembre 1949): 26-31.

(Credit : Paris Match)

For some, the young American woman is a brilliant and adulated creature; for others, she’s disenchanted, vain, superficial, and cold. What is the truth?

These captivating lines opened Paris Match’s 10 September 1949 exclusive on Phyllis Nelson[fn value= »1″]“Phyllis Nelson est une Américaine comme les autres,” Paris Match, no. 25 (10 September 1949): p. 26. My translation of article title: “Phyllis Nelson is an American woman like others.” All translations of quotations in Paris Match hereafter are mine unless otherwise noted.[/mfn], a young Minnesotan transplant in New York who was chosen as the subject for an article that was to settle the French debate about the typical American woman[fn value= »2″]Throughout this essay, when I refer to “America” or “American,” I mean the United States or citizens of the U.S. It should be noted that Paris Match referred to the United States mainly as “Amérique” during the period under study here. Raymond Cartier, Paris Match’s most renowned journalist at the time, wrote a book, Les Quarante-huit Amériques (Paris: Plon, 1953), that demonstrates this usage of the term.For the purposes of this essay, I focus on representations of the “ordinary” or “typical” American woman. Women of the American cultural (fashion, film, music, radio, etc.) and political elite are generally excluded because they were discussed more terms of celebrity journalism than in a cross-cultural, sociological manner.[/mfn] : was she happy and vibrant? Or did she fit the French stereotype of the self-centred tyrant? Nelson was chosen to answer these questions because members of Paris Match’s New York–based team found her to be similar to many other American women whom they had encountered in their research. However, Nelson would not be the only representation of the everyday American woman to appear in Paris Match’s early years of publication. In fact, Paris Match explored the lives and experiences of American women frequently, ultimately serving as a mirror in which “traditional” French identity and gender relations were reflected and refracted in an anxious post–Second World War era increasingly dominated by France’s modernizing “hero-villain,” the United States.

This essay is part of my growing research project on the American imaginary that Paris Match built through its first decade of publication (1949–58)[fn value= »3″]The year 1955 is the cut-off for this essay, due mainly to time constraints. I will be expanding my study to 1958, the year when Charles de Gaulle ushered in a new nationalist movement in France.[/mfn]. Upon close examination of its weekly catalogue of monochromatic photos and a few splashes of colour during this time period, I discovered that Paris Match made “the American” one of the largest elements on its representative map and, in doing so, reworked post-war France’s perceptions of national self and attitudes toward the Franco-American alliance through explicit and implicit comparisons between the United States and France. In this paper, I analyze Paris Match’s textual and visual representations of the American woman through a gendered national lens and uncover the ways in which the American woman was compared to the French woman in order to both entrench and redefine what it meant to be French and a partner in the Franco-American alliance immediately after the war.

Situating Paris Match’s Emergence

Paris Match emerged in a watershed moment of French history. When Jean Prouvost launched the magazine in March 1949, France had been liberated for nearly five years, but the pain of reconstruction after Nazi German occupation and Vichy collaboration still saturated the French collective memory. Many parts of the country faced shortages of food, housing, access to water, and basic amenities of life. Shantytowns developed around large cities, and, with rising inflation, continued confrontations between workers and managers, a tumultuous legal purge of national enemies, and an emerging geopolitical arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union, anxieties about France’s future direction loomed on the national horizon[fn value= »4″]Peter Hamilton, “Representing the Social: France and Frenchness in Postwar Humanist Photography,” in Stuart Hall (ed.), Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (London: Sage, 1997), pp. 88–91. For details about France’s attempt to cleanse itself through its épuration légale (“legale purge”), see Rod Kedward, “Retribution and Closure,” in La Vie en Bleu: France and the French Since 1900 (London: Allen Lane, 2005), pp. 307–09, 312–13; Henry Rousso, “L’épuration en France une histoire inachevée,” Vingtième Siècle: Revue d’histoire, no. 33 (1992), p. 84; Charles Sowerwine, “The Purge,” in France since 1870: Culture, Politics and Society (New York: Palgrave, 2001), pp. 228–32. There were also specific “purges” of journalists (see Kedward, “Retribution,” pp. 312-13; and Fabrice d’Almeida and Christian Delporte, “Faire table rase: l’épuration et ses limites,” in Histoire des médias en France: De la grande guerre à nos jours [Paris: Flammarion, 2003], pp. 140-144.)[/mfn].

![Fig. 2: Unknown author. 1949. «Phyllis Nelson est une Américaine comme les autres» [Photographie]

Paris Match, N. 25 (September 10th 1949): 26-31](/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/1b_correction-scaled.jpg)

Fig. 2: Unknown author. 1949. «Phyllis Nelson est une Américaine comme les autres» [Photographie]

Paris Match, N. 25 (September 10th 1949): 26-31

(Credit : Paris Match)

Yet, by the early 1950s, France was also on the brink of vibrant economic growth and social change[fn value= »5″]Kedward, “The Chequered Imperative of Change, 1940s-1958,” in La Vie en Bleu, pp. 349-383.[/mfn]. Towns and cities were rebuilt, utilities and social support were nationalized, women started to take on roles beyond domestic duties, and new businesses, media, and technology became a part of everyday life. As Charles Sowerwine aptly summarizes the period, “The key fact for most [French] people was that, during the 1950s, American aid, the national plan and worldwide prosperity brought an economic boom that transformed French life at every level [fn value= »6″]Sowerwine, France since 1870, p. 274. This is not to say that all reaped the benefits of France’s rebuilding after the war. As Sowerwine notes, “People still lived in crowded and poor conditions. In 1954, only 58.4 per cent of French homes had running water, 26.6 per cent indoor toilets, 10 per cent baths or showers. . . . Consumer goods were also slow to reach the working class. While in 1954 only 7.5 per cent of households had a refrigerator, by 1959 20.5 per cent had one, but in 1959, only 12.1 per cent of agricultural workers and 21.5 per cent of workers had cars, while 74.3 per cent of professionals and 57.8 per cent of middle managers had them. These visible differences perpetuated a sense that only the rich got richer and maintained a strong sense of class conflict” (pp. 276, 279).[/mfn].” France was on the rebound; it was a society moving inward toward a new middle-class, mass-consumption life[fn value= »7″]Kristin Ross, Fast Cars, Clean Bodies (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995). Interiority is imagery that Ross emphasizes as the main “movement” of the 1950s in France: “The movement inward . . . is a movement echoed on the level of everyday life by the withdrawal of the new middle classes to their newly comfortable domestic interiors, to the electric kitchens, to the enclosure of private automobiles, to the interior of a new vision of conjugality and an ideology of happiness built around the new unit of middle-class consumption, the couple” (p. 11). Also see Kristin Ross, “Starting Afresh: Hygiene and Modernization in Postwar France,” October 67 (Winter 1994): pp. 22–57.[/mfn].

Perhaps one of the greatest facilitators of this process was the United States government’s approximately $2.3 billion contribution to France between 1948 and 1953 through its European Recovery Program, more popularly known as the Marshall Plan after then Secretary of State George Marshall[fn value= »8″] As Irwin Wall notes, “Between 1947 and 1954 the United States and France entered into an intimate relationship characterized by unprecedented American involvement in French internal affairs.” Irwin Wall, The United States and the Making of Postwar France, 1945–1954 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), p. 11.[/mfn]. The Marshall Plan aimed to help France rebuild through intense cultural, economic, educational, and governmental exchange[fn value= »9″]Business and governmental leaders, authors and artists, and everyday workers on both sides of the Atlantic crossed paths through government-sponsored tours and visits. The United States organized official tours to the country for French farmers, factory managers and workers, government employees, teachers, artists, and a variety of other workers and managers from a range of sectors. See Richard F. Kuisel’s chapter “The Missionaries of the Marshall Plan” in Seducing the French: The Dilemma of Americanization (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), pp. 70–102). for a rich description of the exchange programs established as part of the Marshall Plan Program.[/mfn]. The intention was to bring the countries together to share the knowledge, skills, and ideas necessary to help France rebuild, and while the French public generally appreciated assistance, the United States’ notions of post-war American modernity did not go uncriticized. Many French people were ambivalent about American recommendations on how to rebuild, which conflicted with French tradition; others were repelled by explicit political efforts to quell the supposed rise of communism in Western Europe[fn value= »10″]See Brian A. McKenzie, Remaking France: Americanization, Public Diplomacy, and the Marshall Plan (New York: Berghahn Books, 2005).[/mfn]. Irwin Wall sketches the noteworthy tension between the United States and France in the late 1940s and early 1950s:

Antinomies in the two cultures became exaggerated through confrontation: French Cartesianism versus American pragmatism, statism versus private initiative, centralization versus decentralization, a revolutionary myth versus a carefully cultivated myth of national consensus. The United States became the standard of modernization for most nations in the postwar era. The French blamed their traditions for their nation’s relative backwardness, and were invited to internalize an American image of themselves as feudal, archaic, politically unstable, and economically stagnant, a “stalemate society”[fn value= »11″]Wall, United States, p. 11.[/mfn].

Thus, France was in a fruitful Franco-American era that had divisions and anxieties lurking below the surface: “The political battle . . . intersected with the cultural and in both the United States stood for modernization, both hero and villain at the same time”[fn value= »12″]Sowerwine, France, p. 281. As Wall notes, for the French, America was “excessively mechanized, devoted to efficiency and rationalization to the neglect of human values, in short, materialist, capitalist, and imperialist” (United States, p. 11). Americans were drab, conventional, and devoid of individualism. The United States was an uncultured society of “overgrown children imbued with naïve optimism” (United States, p. 11). And although they were pragmatic, Americans were blinded by their sense of superiority and did not have a theoretical understanding resulting from the wisdom of experience in the Old World (United States, p. 12).[/mfn]. It is not surprising that France’s hero-villain would also serve as a major journalistic influence and source of imagery when Paris Match was founded in March 1949[fn value= »13″]Jean-Pierre Bacot and colleagues attribute Paris Match’s emergence to the completion of a mediated loop between the United States and Europe (see Jean-Pierre Bacot et al., “La naissance du photojournalisme: le Passage d’un modèle européen de magazine illustré à un modèle américain,” Réseaux, no. 151 (2008): pp. 9–36). They argue that a nebular form of photojournalism was born in Europe, especially France and Germany, in the 1920s and 1930s, through the proliferation of photo-rich publications that were forced to close shop during the Second World War. Although styles differed, what underlay these early photojournalistic magazines was their use of photographs as complements to text and their focus on “useful knowledge” (Bacot et al., “Naissance,” p. 24). In the United States, Henry Luce’s Life took up and modified this model before and during the war by blending entertainment with useful knowledge through a dominating collage of photographic representations. For Prouvost, Life was one exemplar for a new style of French photojournalism that might be popular with an upwardly mobile mass audience. Life’s regular use of colour photography, monochromatic text, and peppering of advertisements was attractive and new for French readers who had become accustomed to photography but found lacklustre media in a highly government-regulated environment in the early post-war period. Thus, by hiring some of the best journalists and aspiring photographers at the time, Prouvost and Roger Thérond, the young movie section director turned editor-in-chief, made Paris Match a staple of French print media in just a few short years by mimicking Life’s style of photojournalism. According to Norberto Angeletti and Alberto Oliva in Magazines that Make History: Their Origins, Development, and Influence (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2004), “The magazine’s circulation rose fourfold in just a few years, reaching 425,000 in 1951, 700,000 the following year, 900,000 in 1953, 1.2 million in 1954, and 1.4 million in 1955” (p. 192), and the magazine became known for its slogan, “Weight in words, shock in photos” (“le poids des mots, le choc des photos”). Paris Match is still published today, with an approximate weekly circulation of over 600,000; however, its etablishment as a staple of modern French media came through its initial years modelled after its American cousin Life (Groupe Lagardère, “Les sociétés et marques du groupe: Paris Match,” 24 November 2010 http://www.lagardere.com/groupe/societes-et-marques/societes-et-marques-…).[/mfn]. What has not been explored in Paris Match’s early history, though, are images of America such as that of Phyllis Nelson and how this new form of French photojournalism discursively attempted to entrench French national identity in traditional gender roles amid the anxieties of rapid post-war change. Before examining this mediated imaginary, however, theoretical lenses from the literature on nationalism and social comparison are needed.

Theories of Nationalism and Social Comparison

In his recent study of reality television and how women’s bodies in the media come to represent a contested terrain of national and international politics, Marwan Kraidy writes, “Women are reproducers of the nation and at the same time markers of boundaries between the nation and its others”[fn value= »14″]Marwan M. Kraidy, Reality Television and Arab Politics: Contention in Public Life. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 162.[/mfn]. As noted above, in the early 1950s, the United States played an important role in French reconstruction, but there were divisions and anxieties in France about American influence. One way in which Paris Match dealt with this tension was the representation of the American woman, which not only served as a comparative benchmark for the French woman and French gender relations more generally, but also was a symbolic marker of difference between France and the United States[fn value= »15″]At this point in my research, I am not assuming this nationalist discourse was intended or planned by the editors, journalists, and photographers of Paris Match.[/mfn].

![Fig. 3: Unknown author. 1949. «Phyllis Nelson est une Américaine comme les autres [2]»

Paris Match, N. 25 (September 10th 1949): 26-31](/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/1c_correction-scaled.jpg)

Fig. 3: Unknown author. 1949. «Phyllis Nelson est une Américaine comme les autres [2]»

Paris Match, N. 25 (September 10th 1949): 26-31

(Credit : Paris Match)

Maria Todorova’s work on constructions of national self through a mediated Other provides insight into understanding how the American woman could serve as an imagined symbolic division between the United States and France. In her analysis of Western European travel writing, popular culture, and political rhetoric from the seventeenth century to the mid-1990s, Todorova shows how a mediated image of “the Balkans” has been frozen over the longue durée to create a tribal, backward, and unstable Other for Western Europe’s reconstitution of the national and modern self. Originally a geographic inaccuracy that lumped southeastern Europe into a single region under the thumb of Turkish rule, “the Balkans” by the turn of the nineteenth century was a term “saturated with political, social, cultural and ideological overtones . . . [with] pejorative implications”[fn value= »16″]Maria Todorova, « The Balkans: From Discovery to Invention ». Slavic Review, vol. 53, no. 2, (1994): p. 461.[/mfn] . Eventually, the label was dissociated from its original object and came to be used as the common misplaced symbol of national unrest, instability, and backwardness that that allowed Western Europeans to imagine themselves as culturally superior.[fn value= »17″]Ibid.[/mfn] The Balkans were conceived to be not quite “Oriental” but not quite “civilized Europe”; as such, its lowered position in the Western imagination was propagated by official government statements and popular cultural forms. Paris Match’s representations did not function in the way that Todorova describes. Todorova analyzes a more dominant group’s representations of its “subordinate Other,” whereas Paris Match was a cultural product from a country in a “subordinate” position vis-à-vis its more powerful American object. However, Todorova’s bracketing of the texts and images that frame a representation of another nation in order to see if there is any imaginative, divisive power constituting a mediated sense of national self is a tool useful for analyzing Paris Match’s American woman.

Floya Anthias and Nira Yuval-Davis provide an important analytical addition by bringing the question of gender more clearly into the picture. In the view of these authors, assuming that all women are constructed and implicated similarly in the policies and discourses of the state and nation is narrow-minded[fn value= »18″]Floya Anthias and Nira Yuval-Davis, « Woman-Nation-State » in John Hutchinson and Anthony D.Smith (eds), Nationalism: Critical Concepts in Political Science,(New York: Routledge, 2000), p. 1480.[/mfn] . They stress analytically useful categories to examine how “women have tended to participate in ethnic and national processes in relation to state practices”[fn value= »19″]Ibid. p. 1480.[/mfn]. For the purposes of this paper, two categories are useful analytic tools: “[Women are used] as signifiers of ethnic/national differences – as a focus and symbol of ideological discourses used in the construction, reproduction and transformation of ethnic/national categories . . . [and] as participants in national, economic, and political struggles”[fn value= »20″]Ibid., pp. 1480–81.[/mfn]. Whereas Anthias and Yuval-Davis define women as signifiers of national difference and participants in the struggle or battle for national liberation, the case of Paris Match involves a symbolic “battle” through print media.

The media’s use of gender as a symbolic weapon is showcased well in Agnieszka Graff’s paper on the place of gender talk in constructing the Polish nation amid debates over Poland’s accession to the European Union (EU)[fn value= »21″]Agnieszka, Graff, « The Land of Real Men and Women: Gender ». Journal of the International Institute, (Fall 2007): pp. 10–11.[/mfn]. In her analysis of popular Polish magazines from 2002 to 2005, Graff reveals that these magazines tended to project accession anxieties onto their observations of gender and sexual relations. The EU question threatened the Polish nation’s sovereignty at a time when sexual minorities and women’s contributions outside of traditional spheres of domesticity were becoming more prominent and naturalized. To rationalize the seemingly emasculating loss of sovereignty, magazines used sexual minorities and the new Polish woman as displaced release valves. Instead of dealing with the anxieties of European integration head-on, the magazines, especially conservative ones, called for a return to traditional values in which sexual minorities and women knew “their place” within the confines of traditional (male-dominated) Polish society. Graff summarizes, “[The magazines had an] obsessive concern with gender and the process of Poland’s EU accession . . . anxieties evoked by Poland’s EU accession have been projected onto, and resolved within, the realm of gender »[fn value= »22″]Ibid., p. 10.[/mfn].

In post-war Paris Match, the white, middle-class, upwardly mobile American woman was compared directly or implicitly to the white, middle-class French woman in order to address the ideological struggle playing out within French society over how to rebuild France and the parallel changes in gender roles. The ways in which the American woman was represented ultimately led to comparisons with and reflections on the French woman and served as an imaginary space within which French readers could grapple with post-war anxiety over reconstruction in a context in which American ideas and approaches dominated French society and usurped its former place as a global bastion of culture and progress[fn value= »23″]I do not intend to insinuate that all French readers read and interpreted Paris Match in the same manner. In my expansion of this project, I hope to uncover details on how French audiences received and reacted to Paris Match’s representations of the American woman. In the « woman debate of 1950 » (see below), readers reacted critically and with fervour by writing regular letters to the editor.[/mfn].

This appropriation of the American woman to demarcate and resolve French post-war anxieties requires further exploration of the ways in which social comparison and self-appraisal play out in the context of nationalism. According to Vincent Yzerbyt and colleagues, social comparison is “a core element of human life . . . because comparing oneself to others is the most favored way people use to evaluate” where they stand in relation to others – how they can motivate themselves to aspire to do better than others and discover ways to enhance their sense of self-esteem over others[fn value= »24″]Vincent Yzerbyt et al., « Social Comparison and Group-Based Emotions » in Serge Guimond, ed., Social Comparison and Social Psychology: Understanding Cognition, Intergroup Relations, and Culture, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009 ), p. 174.[/mfn]. Dominic Abrams and Michael Hogg’s discussion of classical social identity theory is also helpful to “explain intergroup relations in general, and social conflict in particular”; these authors argue that “(1) people are motivated to maintain a positive self-concept; (2) the self-concept derives largely from group identification . . . and thus (3) people establish positive social identities by comparing the in group favorably against out groups”[fn value= »25″]Dominic Abrams and Michael A. Hogg, Social Identity and Social Cognition (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 1999), p. 42.[/mfn].

Thus, in Paris Match’s early years, the representations of the American woman served as a way for the magazine to create a positive self-concept for French women and French readers more generally. By comparing the American woman to the French woman in a certain, perhaps questioning, style, French readers could imaginatively compare themselves as an “in group” to the ever-present American “out group” seen regularly in the magazine. As they grappled with the anxiety that came with rebuilding France, the American woman helped them evaluate where France stood in relation to its American allies, explore how the country could aspire to do better, and discover ways to enhance the French national self over that of the overbearing American.

![Fig. 4: Unknown author. 1949. «Phyllis Nelson est une Américaine comme les autres [3]»

Paris Match, N. 25 (September 10th 1949): pp. 26-31](/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/1d_correction-scaled.jpg)

Fig. 4: Unknown author. 1949. «Phyllis Nelson est une Américaine comme les autres [3]»

Paris Match, N. 25 (September 10th 1949): pp. 26-31

(Credit : Paris Match)

Through the American Woman, La Femme Française

The earliest, most in-depth look at the American woman in Paris Match took as its subject Phyllis Nelson, a twenty-five-year-old Minnesotan transplant in New York. According to Paris Match’s New York–based team, which had searched for a typical young American woman who fit “official statistics” of size, origin, education, salary, tastes, and morals, Nelson was deemed perfect because she exemplified all of the American women whom they had encountered: “In her habits and mentality, Phyllis Nelson is identical to millions of young people who fill offices and shops not only in New York City, but throughout the United States. This is not the Miss America of beauty pageants, it’s Miss America in real life”[fn value= »26″] »Phyllis Nelson: Une Américaine comme les autres », p. 25.[/mfn].

Above these opening lines, the title, “Phyllis Nelson: An American Woman Like Others,” immediately invokes what early-twentieth-century American journalist and critic Walter Lippmann calls the filter of the media that creates a certain value in constructing social reality for its audiences 1Lippmann’s seminal work Public Opinion stresses this important filtering role of the media quite clearly: “For the real environment is altogether too big, too complex, and too fleeting for direct acquaintance. . . . To traverse the world men must have maps of the world . . . [and] what each man does is based not on direct and certain knowledge, but on pictures made by himself or given to him” (Walter Lippmann, Public Opinion [New York: The Free Press, 1965], pp. 11, 16).. By emphasizing in large, bold type that almost all American women had the same experience as this one aspiring-to-be-middle-class white woman, Paris Match immediately insinuates a very powerful message regarding women in the United States: the typical American woman was white, most likely from a rural town, and moved to the big city (with her father’s permission) to work as a secretary and find a husband.

A perfected outward appearance was an important aspect of Phyllis’s everyday life.

In addition to the story’s reductionist nature, the article fits the period’s preoccupation with the everyday2For a discussion of post-war France’s interest in the quotidian, see Lynn Gumpert, The Art of the Everyday: The Quotidian in Postwar French Culture (New York: New York University Press, 1997). Others make similar observations; see Yale French Studies’ special issue on “Everyday Life” (No. 73, 1989); Henri Lefebvre and Christine Levich, “The Everyday and Everydayness,” Yale French Studies, No. 73, Everyday Life (1989): pp. 7–11.. The article briefly summarizes Nelson’s upbringing in Minnesota and then focuses on what French readers might have seen as exotic features of her everyday life: ironing her clothes and dressing in the morning, eating a sandwich and drinking a glass of milk for lunch, working with her supervisor, putting on nail polish, living with female roommates, and going out on a date with a man in an open convertible. Everything about Phyllis points to the brilliant, adulated woman in the French imaginary of the United States. Phyllis pulled herself up by her Midwestern bootstraps and paid an exorbitant monthly rent of $17.253“Phyllis Nelson: Une Américaine comme les autres”, p. 26. In 2011 dollars, this is equivalent to about $160 (Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, “What is a dollar worth?” (note : 26 May 2011 is the date of access). http://www.minneapolisfed.org/).. However, this did not stop her from regularly (and “vainly”) spending nearly triple that amount on going-out dresses priced at nearly $504In 2011 dollars, this is equivalent to about $460 (Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis).. Thus, a perfected outward appearance was an important aspect of Phyllis’s everyday life, as it was for all Americans: “Phyllis Nelson wears tailored clothing, like everyone in America, which doesn’t keep her from buying relatively expensive dresses”5Ibid., p. 27.. Moreover, books on good manners (as dictated by a fashion magazine such as Vogue) appeared to be on a par with the great works of literature: “Her library ranges from mystery novels to history books, from The Key to Dreams, a book on manners published by Vogue, to the works of Shakespeare and some classics”6Ibid. p.27..

But the life of the American woman was not all a bed of roses, as one might assume from the article’s photographs featuring smiling poses and material opulence. To conclude the journey into Nelson’s everyday life, the magazine draws a bridge to her “big ray of sunshine” – dating, an “institution accepted, recognized, and approved of throughout the United States”7Ibid., p. 25.. Implying that all American women’s success was based on their triumphs in dating, the article highlights anxiety that American women felt about not being married. Fortunately, Phyllis was the perfectly successful American woman, as she had six or seven boyfriends. In fact, she told the reporters that she would do anything she could not to be included among the 10% of the American female population who were single. Phyllis was lucky, though. In the final three-quarter-page photograph that draws the article to a close, Phyllis rests her head on her boyfriend’s shoulder and gives him a smile. She appeared content with her life as an American woman who has an uneasy sense of independence – her can-do attitude and her self-worth being dependent on her relationship with a man.

Beyond the attempt to have Phyllis Nelson represent (and reify) the typical American woman, the article makes implied comparisons with France. Again, these comparisons were not mere points of translation for a French audience. Rather, as Todorova, Graff, and the definitions of social comparison might suggest, such comparisons served to situate and define French readers’ sense of national self; they also brought readers closer to the American woman while distancing them from disturbing or disapproved-of aspects of American life. This is evident in the article’s focus on Nelson’s salary and spending habits, practically down to the penny, for items such as her daily breakfast of fruit juice and coffee. By shockingly spending over half of her salary on rent, Nelson faces a living situation contrary to what was found in France: “And the rent! As in all countries of the world, except France today, rent in the United States, and particularly in New York, is the main component of individuals’ budgets”8Ibid., p. 26. Emphasis added.. Thus, the United States was different from France, the difference is much more troubling than the high cost of rent. Phyllis’s materialism was disconcerting because it left her broke, and she therefore had to reduce her food budget. Even though, “like the majority of American men and women, her body and clothing are perfectly clean,” Nelson is a slave to the Key to Dreams of material goods, technology, and her quest for marriage, which, from the French perspective, is exotic yet disquieting.

The American woman was covered and debated in other issues of Paris Match as well. The magazine’s premier New York-based journalist, Raymond Cartier, started a heated debate in May 1950 about who was better off – American or French women – in his feature “The American Woman – Is She the Unhappiest in the World?”9Raymond Cartier, “La femme américaine—est-elle la plus malheureuse du monde?” Paris Match, No. 59 (6 May 1950): pp. 18-19. Cartier cites the increase in the ratio of American women to men after the two world wars as one major cause of their misery. American women were in constant competition for the perfect man who was a “good provider” of materialistic wealth. Yet, in Cartier’s view, the American woman was the most privileged in the world because of her material comforts: “There certainly is no more privileged creature in the world than the American woman . . . [she] is certainly the best nourished, best dressed, best housed, best cared for, best protected, the richest, the most respected, and the most coddled in the world”10Ibid. pp. 18-19..

Cartier seems to be most troubled by American women’s holding the upper hand in gender relations, particularly because divorce held out the prospect of alimony, and husbands were required to do all of the chores around the house while their wives performed symbolic petits services and pampered themselves with beauty products. But what Cartier constructs as American women’s unhappiness was the lovelessness of their marriages and the corset-like restriction of relying on their husbands. Many American women felt that they were treated like sex objects or a member of their husband’s personal “harem” because husbands wanted sex more than romance. Even more disappointing for women was the docile nature of American men, who offered their wives everything they wanted (except romance), when what women really wanted was independence. Cartier concludes, “The American woman is the most miserable creature in the world . . . the excesses of her well-being, privileges, and domination have not given her the freedoms about which feminists of the last century dreamed”11Ibid. pp. 18-9.. Thus, being dependent on their men who did more complex tasks around the house while they contented themselves with doing everyday household chores and using their new electric appliances left American women bored and looking for romance with a strong manly figure12Earlier that year, in a profile of Washington, D.C., Bess Truman, former President Harry Truman’s wife and right-hand “man,” is classified as the prototypical bossy American woman, presumably by Cartier: “[Bess] is exactly the prototype of the hundreds of thousands of women who govern America, much more than the Capitol and the White House combined, in terms of regulating morality and dictating education by imposing their notions of good, bad, decency, inappropriateness, virtue, and sin” (Paris Match, “Washington: capital du monde et sous-préfecture,” No. 106 [31 March 1951], pp. 23, 25)..

![Fig. 5: Unknown author. 1949. «Phyllis Nelson est une Américaine comme les autres [4]»

Paris Match, N. 25 (September 10th 1949): 26-31](/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/1e_correction-scaled.jpg)

Fig. 5: Unknown author. 1949. «Phyllis Nelson est une Américaine comme les autres [4]»

Paris Match, N. 25 (September 10th 1949): 26-31

(Credit : Paris Match)

Like the Phyllis Nelson feature, Cartier’s piece makes an implicit comparison between American women, who were miserable despite their material luxuries, and French women, who were, thus, implicitly less miserable. By focusing in absolute terms on the frenetic competition among American women, Cartier implicitly exalts a large body of his readership, French women, who did not fit this bossy, materialistic extreme. American women were miserable because they were the victims of their own modern freedoms. More problematic for Cartier is the fear that the American woman provoked in French men. In an image adjoining Cartier’s article, an American cartoon shows a wife pointing a gun at her husband to remind him that he needs to take their son to school. This image is reminiscent of a Paris Match issue of 8 October 1949, in which French actress Michèle Morgan points a double-barrel shotgun at readers on the front cover. Perhaps coincidentally, several pages into the issue, an article discusses the rise of feminism and women’s bold, direct, demanding “revenge” on men. According to the article’s authors, the worst aspect was the enslavement of French men by women, similar to the enslavement of American men:

The fate that awaits the French man is already decided. There is an example before our very eyes: the American male. . . . When an American man speaks to an American woman, he always speaks like a slave to his master (hence his incredibly rude reactions to non-American women when [he’s] abroad). Most often, the husband cares for children in the evening, while the woman reads a scholarly work or goes to her club.

The writer Henri Troyat, who recently toured America, states that he was deeply struck by the happy, calm expression of American women. Compared to American women, he found French women to be worried, or even in anguish. . . . The American writer Gore Vidal summed up the situation succinctly: “In America, we are led by women. Most men are emasculated and no more dangerous than pet dogs”13“L’heure des femmes a sonné”, Paris Match No. 29 (8 October 1949): pp. 34-5..

Therefore, French men were portrayed as fearful of post-war shifts in gender roles. One view might be that American women were happy, like Phyllis Nelson with her independence and material luxuries, whereas French women were miserable, worried, and wanting “revenge.” Cartier’s view, in contrast, is that American women were miserable due to their domination and boredom. In declaring American women miserable, he implicitly argues that American gender relations were problematic. He, too, fears the fateful shackles to come for French men, so he declares American women miserable in order to make the “traditional” positions of French men and women admirable and desirable.

Cartier’s sketch of the miserable American woman did not go unchallenged. On 24 June 1950, Margaret Gardner, an American living in Paris, was given the opportunity to respond; in her article, she claimed that French women were miserable, too14Margaret Gardner, “Vous vous trompez, monsieur Cartier! Ce sont les Françaises qui sont malheureuses,” Paris Match No. 66 (24 June 1950): pp. 22–23.. She notes that Cartier’s caricature of the overburdened American man, who wakes up first to fetch his wife a grapefruit and then take the children to school, only reveals Cartier’s anxieties as a Frenchman. In Gardner’s view, Cartier is worried about troubling gender role reversals that could come to France: “Because, as you yourself, a Frenchman, said, in housework, it’s [the American woman] who wears the pants . . . or, rather, it’s [the American man] who wears the apron”15Ibid. pp.22-3..

Gardner attributes Cartier’s calling the American woman “exceptional” to his belief in “her rarity” and the docility of the American man: “The American man, if he is fortunate enough to find a woman, places her in a shrine, free of dust from the cellar and the insults of laundry.” Gardner, rather, finds this a grave misunderstanding of American gender relations: “And you owe this opinion [of American men’s docility] to Western films that you saw in your childhood. In the saloon where gold rushers and cowboys went to drink there was always a blond girl, who had just gotten off the paddleboat, for whom men would kill each other”16Ibid., p. 23..

Continuing with imagery of fighting men, Gardner states that Frenchmen, who proudly claimed that they invented chivalry, were not chivalrous at all. French women were dependent upon their husbands to determine their identities and approve of everyday business such as banking and applying for a passport. In France, women were still considered inferior to men: “There remain in Latin countries [such as France] some vestiges of the ancient Roman conception of the inferiority of women. In the United States, these have been forgotten”17Ibid. p.23.. For Gardner, Cartier’s insistence that American women were unhappy because their husbands and modern appliances freed up time to make themselves pretty was nonsense. French women were miserable because they were left in silence, and while Gardner admits sarcastically that American women can be bossy, why was that so bad when even the Duke of Windsor had renounced the throne for a “femme made in the U.S.A.”? Her ironic solution is to create the perfect misery-loves-company couple: Cartier’s dominated American man and what Gardner sees as the suppressed French woman.

It is important to note here that Paris Match created a space for Margaret Gardner, an American woman, to counter directly Cartier’s view of the “miserable American woman.” By having an American woman engage candidly in a debate about gender relations in the United States compared to those in France, Paris Match enabled its readers to face the larger tension built into Franco-American relations. Gardner contradicts Cartier by showing the ways in which French women were enslaved to their men and to lives of technological and consumer self-deprivation. Because the magazine included Gardner in this debate, readers could engage in the magazine’s regular comparison between the United States and France and see the bias of the other side openly. This was tactically smart, as injecting an American voice critical of French women’s lives might inspire strong reactions among French readers to assert their notion of Frenchness, countering the view of an opinionated Américaine.

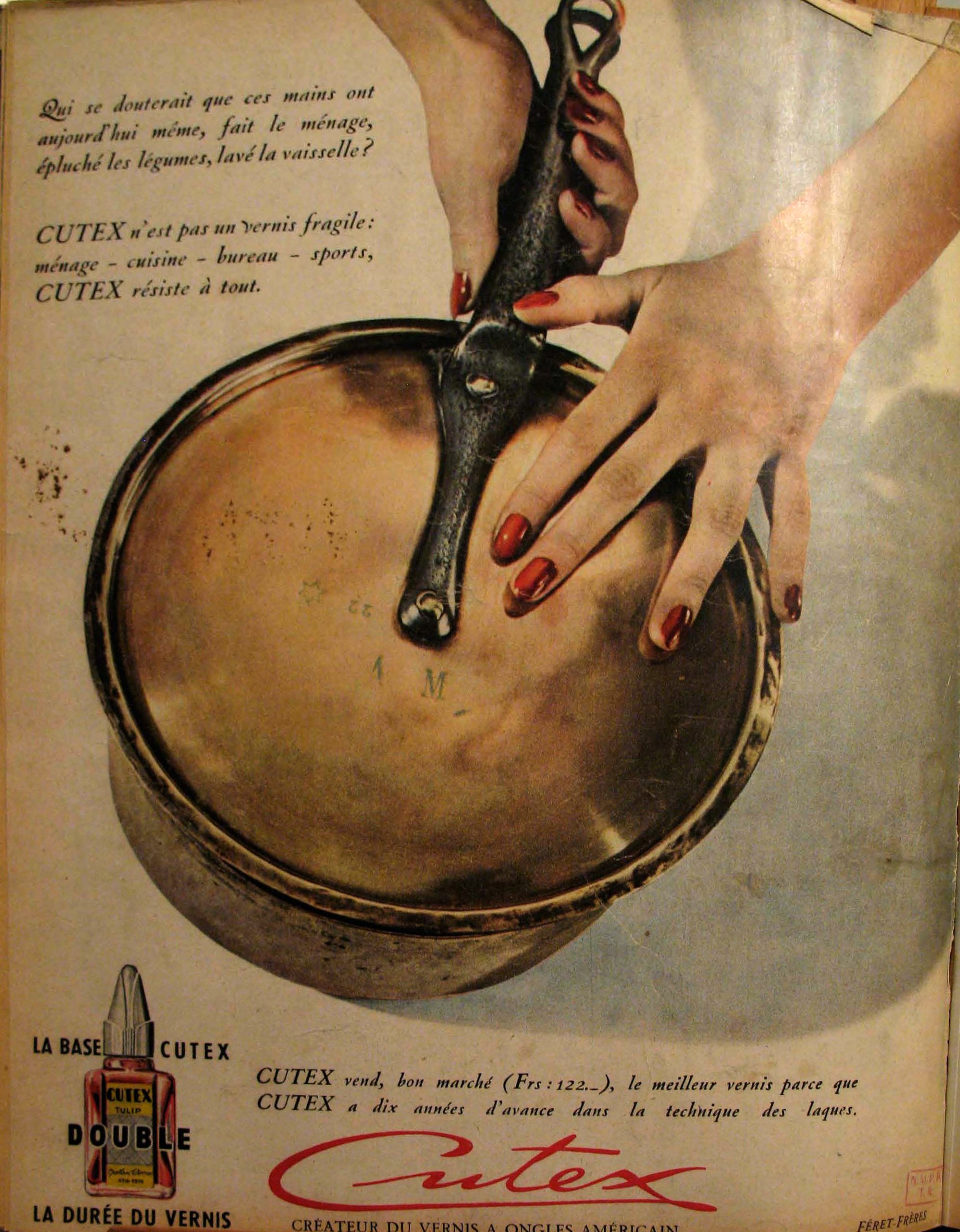

Fig. 6: Auteur inconnu. 1951. «Cutex ad»

Paris Match. No. 100 (17 février 1951): 49

(Credit : Paris Match)

Such reactions were revealed on 22 July 1950, when Paris Match concluded the “woman debate of 1950” through a one-page summary of the “abundance” of letters to the editor sent by “deeply moved” French women 18“La Française est la plus heureuse: les lecteurs de ‘Paris-Match’ donnent leur avis sur le bonheur conjugal”, Paris Match, No. 70 (22 July 1951): p. 24.. The article’s page-centred headline proclaims, “The French Woman is Happier”19Ibid. p.24.. The reasons are featured in bold type: French women knew how to cook without the constraints of machines (“She knows how to flip pancakes”), they did not hide behind make-up and false happiness (“Her make-up doesn’t lie about her physical being”), and they shared their freedom with their husbands rather than making their husbands do everything (“No husband happy to do everything”)20Ibid. p. 24.. One letter provides an apt summary of what the magazine views as the dominant French woman’s sentiments regarding American women’s dependence on technology and their husbands:

Mrs. Isabelle Blanchard, of Grenoble, hopes that American women will never know years such as those that French women experienced during the Occupation. “Because if, in America, it’s the husbands who do everything, with the help of their electric appliances,” she said, “I wonder what American women would do with a half-hour of electricity each day (in good times) and their husband absent. They probably would blow their brains out21Ibid. p.24..

Blanchard’s and Paris Match’s representation of the technologically oppressed and emotionally depressed American woman was very revealing at this moment in French history. As Blanchard’s letter shows, the memory of German occupation was still fresh in the French mind, especially amid the flurry of new household products, many of them American, that not only flooded France’s storefronts and shelves, but were advertised in Paris Match. As Paris Match gained its footing within France’s print culture, products such as Hoover vacuum cleaners, compact clothes washers, Hollywood’s Max Factor Pan-Cake Make-Up, American-style Spray-Net, the Pennsylvania oils in Dr. Roja Shampoo, and Kelvinator refrigerators from Detroit filled an ever-growing number of pages. Certainly, France was on its way to becoming consumer-based society, but, as Paris Match revealed through the “woman debate of 1950,” ambivalence remained toward new timesaving and beautifying products given the cultural memory of the recent past. For French women, new products could certainly save time and make one beautiful, but it would pull them away from the realities of everyday life and provide a new kind of enslavement to their machines and their men.

![Fig. 7:Auteur inconnu. 1949. «Frigidaire ad» [Publicité]

Paris Match, No. 209 (21 mars 1953): 49](/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/3_correction.jpg)

Fig. 7:Auteur inconnu. 1949. «Frigidaire ad» [Publicité]

Paris Match, No. 209 (21 mars 1953): 49

(Credit : Paris Match)

Yet a French woman’s choosing the “American way” could have far graver consequences than enslavement. Amid the Cartier-Gardner debate, a short article on 1 July 1950 reveals what could happen when a French woman becomes Américaine22“Elles sont parties Françaises, elles reviennent Américaines”, Paris Match, No. 67 (1 July 1951): pp. 8-9.. In a deliberation of whether “war brides” – French women who married American soldiers during or after the war – were truly happy, the magazine presents the story of Madeleine Lavery, who married a soldier from California. Upon leaving Paris to move to her husband’s family farm in the Sierra Nevada in California, Madeleine was welcomed by her in-laws and found success by becoming a “cover girl”; her income, added to her husband’s modest salary, made it possible to buy a Frigidaire, a Ford, and a television. The article concludes, however, that Madeleine’s newfound American life and material riches did not provide complete happiness, as her parents disapproved of her marriage and her move to the United States. When she arrived at Paris’s Orly Airport with her son William, her parents did not come to pick her up; she was rejected by her immediate family, and at the time the article was published, she did not know if her parents would visit her. “Perfect happiness!” the article concludes about the transformation of a beautiful French woman into a successful Américaine.

French women who married American soldiers during or after the war – were truly happy.

Conclusion

In its first six years of publication, Paris Match paid attention regularly to the everyday American woman. Each photograph and article was meticulously crafted by Paris Match’s entourage of editors, journalists, and photographers, and how they represented the American woman reveals one reading of French cultural memory and the preoccupations about the post-war present and future that they saw around them in the early 1950s.

Before Prouvost’s editorial team was the United States, France’s aspiring cousin, which took on an important role in global affairs after the Second World War. America was France’s hero-villain, and Paris Match similarly constructed a United States that was admirable yet troubling. The United States offered many great advances, but it also presented a troubling mirror in which the French could reflect on their own worries about a future that eschewed tradition and pressed the questions of new gender roles in an increasingly mechanized, commercialized society. Paris Match also refracted the ever-changing experiences that French society was going through and would most likely have to live with in the future. Thus, criticizing the “excessive freedoms” of American women such as Phyllis Nelson, with her dependence on material goods and modern technology, propped up French traditions against America’s commercial and military predominance. However, in using the American woman to create a release valve for anxieties over Franco-American tensions, Paris Match ironically legitimized the plethora of advertisements of modernizing household and beauty products filling its pages and paying for its publication.

Ultimately, in order to navigate a sense of what Paris Match saw as the French place in an intense Franco-American moment after the Second World War, one must examine how Paris Match appropriated the American woman. Paris Match emerged in the post-war period inspired by the American magazine Life, but it served as a physical manifestation of French cultural memory and an imaginary space representing what France could and should not be through the American woman. Looking to this imaginaire is important because it reveals how the magazine represented and drew on the French cultural horizon to grapple with its recent past and intensified relationship with the United States. Most importantly, though, a gendered national lens paired with concerns of social comparison presses the examination of how the magazine situated France vis-à-vis the United States through its representations of America at a moment when recent traumatic events pressed French society to look back introspectively so it could move forward with its reconstruction and reconciliation. For Paris Match in its first six years of publication, the United States was a hero filled with intriguing personalities, such as Phyllis Nelson, who could be presented in an exciting, informative stylized form of print media, but such heroines were also troubling villains who exposed the dark underbelly of Americanized life that could and would come to haunt the French in the future.

References

[s. a.]. 1949. Paris Match.

- 1Lippmann’s seminal work Public Opinion stresses this important filtering role of the media quite clearly: “For the real environment is altogether too big, too complex, and too fleeting for direct acquaintance. . . . To traverse the world men must have maps of the world . . . [and] what each man does is based not on direct and certain knowledge, but on pictures made by himself or given to him” (Walter Lippmann, Public Opinion [New York: The Free Press, 1965], pp. 11, 16).

- 2For a discussion of post-war France’s interest in the quotidian, see Lynn Gumpert, The Art of the Everyday: The Quotidian in Postwar French Culture (New York: New York University Press, 1997). Others make similar observations; see Yale French Studies’ special issue on “Everyday Life” (No. 73, 1989); Henri Lefebvre and Christine Levich, “The Everyday and Everydayness,” Yale French Studies, No. 73, Everyday Life (1989): pp. 7–11.

- 3“Phyllis Nelson: Une Américaine comme les autres”, p. 26. In 2011 dollars, this is equivalent to about $160 (Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, “What is a dollar worth?” (note : 26 May 2011 is the date of access). http://www.minneapolisfed.org/).

- 4In 2011 dollars, this is equivalent to about $460 (Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis).

- 5Ibid., p. 27.

- 6Ibid. p.27.

- 7Ibid., p. 25.

- 8Ibid., p. 26. Emphasis added.

- 9Raymond Cartier, “La femme américaine—est-elle la plus malheureuse du monde?” Paris Match, No. 59 (6 May 1950): pp. 18-19.

- 10Ibid. pp. 18-19.

- 11Ibid. pp. 18-9.

- 12Earlier that year, in a profile of Washington, D.C., Bess Truman, former President Harry Truman’s wife and right-hand “man,” is classified as the prototypical bossy American woman, presumably by Cartier: “[Bess] is exactly the prototype of the hundreds of thousands of women who govern America, much more than the Capitol and the White House combined, in terms of regulating morality and dictating education by imposing their notions of good, bad, decency, inappropriateness, virtue, and sin” (Paris Match, “Washington: capital du monde et sous-préfecture,” No. 106 [31 March 1951], pp. 23, 25).

- 13“L’heure des femmes a sonné”, Paris Match No. 29 (8 October 1949): pp. 34-5.

- 14Margaret Gardner, “Vous vous trompez, monsieur Cartier! Ce sont les Françaises qui sont malheureuses,” Paris Match No. 66 (24 June 1950): pp. 22–23.

- 15Ibid. pp.22-3.

- 16Ibid., p. 23.

- 17Ibid. p.23.

- 18“La Française est la plus heureuse: les lecteurs de ‘Paris-Match’ donnent leur avis sur le bonheur conjugal”, Paris Match, No. 70 (22 July 1951): p. 24.

- 19Ibid. p.24.

- 20Ibid. p. 24.

- 21Ibid. p.24.

- 22“Elles sont parties Françaises, elles reviennent Américaines”, Paris Match, No. 67 (1 July 1951): pp. 8-9.